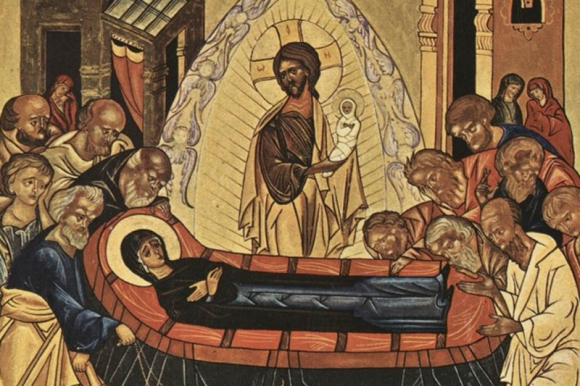

THE PARADOX OF THE DORMITION

(Friday, August 15)

“In you the laws of nature (τῆς φύσεως οἱ ὅροι, естества уставы) are defeated, O pure Virgin: from virginity comes childbirth, and life is introduced by death. After bearing, a virgin, and after dying – living, ever saving, O Mother of God, your inheritance.” (Ode 9, Byzantine Canon of Dormition)

The Theotokos defies our usual expectations of physical reality, which is why we can call her life ‘paradoxical.’ The word ‘paradox’ (from the Greek words ‘para,’ meaning ‘beyond,’ and ‘dokeo,’ meaning ‘expect’) means something beyond our expectation; a kind of thing we would not expect, like a virgin giving birth, or life springing from death.

We would also expect that she, as a Jewish woman of the first century, would necessarily be subject to some man, either her father or her husband. But this was not quite the case. Sure, she was assisted in her vocation by certain people, (as are we all), at different stages of her life. There were her parents, by whom she is led into the Temple, but really it is her vocation that *led them* to parent this daughter in the way that they did, in their old age. Then there were the priests in the Temple, by whom she is led to be betrothed to Joseph, in the earlier years, but we see that Joseph is led by her vocation, not the other way around, and not because she is bossy. God was leading the way. Finally, there is John the beloved disciple, whom she is told by the crucified Lord henceforth to “mother,” which is a position not of subjugation but of authority. No merely-human being ‘had’ the Mother of God in the sense that women at the time belonged to someone, which is a thing we would not expect. One sees in her cross-carrying journey, throughout which she is *obedient* to the vocation that came not from men but from God, that she remains free in her obedience, which is also a paradox, because we might think that freedom and obedience don’t mix. Even after her dormition, we don’t ‘have’ her body to venerate as holy relics. It was taken up or ‘assumed’ (as the Roman Catholics call this) into heaven by her Son, because even death could not hold her physically.