“Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are. (John 17:11)”

“Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are. (John 17:11)”

After the Resurrection, Jesus appeared to his followers for forty days. He did not live with them on a day to day basis, as he did before his crucifixion and death, but he rose now into glory, giving us also the hope of resurrection to eternal life. His appearances had a particular goal, as he explained later in the Gospel of John, but in the same discourse we have heard today, “As you sent me into the world, so I sent them into the world. (John 17:18): The Gospel today begins, “Father, the hour has come. Give glory to your son, so that your son may glorify you, just as you gave him authority over all people, so that he may give eternal life to all you gave him” (John 17:1-2). In the Gospel of St. Matthew, as Jesus leaves his followers, he give them this commission, “All power in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:18-19). After his crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus is glorified, he has all power and authority, and he passes on his mission to us by giving us the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

Some of the Fathers of the Church have asked the question: “Why didn’t our Lord stay with us in his risen glory and give us clear guidance in the building up of his kingdom? Why did he leave us and return to the Father, where as God he reigns with the Father eternally, and now sits at his right now also in the human nature that he took for our salvation?” We might muse – it certainly would make it easier for us if Jesus stayed visibly with us and would be the power of our faith in the world. He left us, though because of God’s wisdom. If he stayed with us, we might perceive him as a tyrant, but his whole earthly mission was exactly NOT to establish an earthly political kingdom, but to establish the Kingdom of God, which can exist only in an atmosphere of complete human freedom. In other words, it is now up to us, by loving God and our neighbor freely, by freely doing the will of God to build up this kingdom. At the same time, God did not leave us entirely on our own. He promised, I tell you the truth, it is better for you that I go. For if I do not go, the Advocate will not come to you. But if I go, I will send him to you. (John 16:7)” We have received the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, in our baptisms. The priest has anointed us with chrism, saying, “The gift of the Holy Spirit.” Again, St. John teaches, “As for you, the anointing that you received from him remains in you, so that you do not need anyone to teach you. But his anointing teaches you about everything and is true and not false; just as it taught you, remain in him” (1 John 2:27). We cannot build up God’s kingdom by our own human strength, but only by the power of the Holy Spirit given to us.

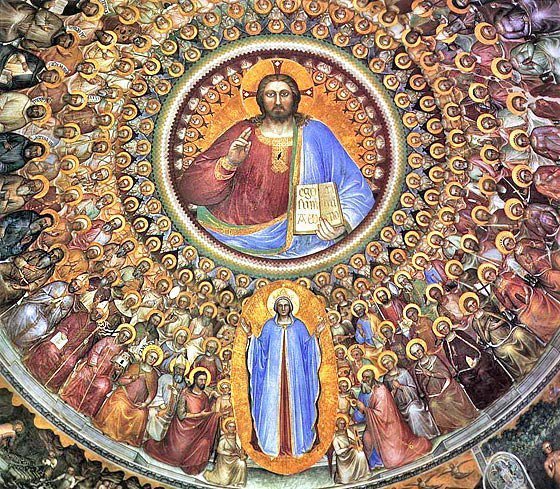

The Greek Church celebrates the great company of saints today. The Latin Church celebrates All Saints on November 1.

The Greek Church celebrates the great company of saints today. The Latin Church celebrates All Saints on November 1. ***Nota Bene: Divine Liturgy this morning at 9:00 a.m.

***Nota Bene: Divine Liturgy this morning at 9:00 a.m. “Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are. (John 17:11)”

“Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are. (John 17:11)”

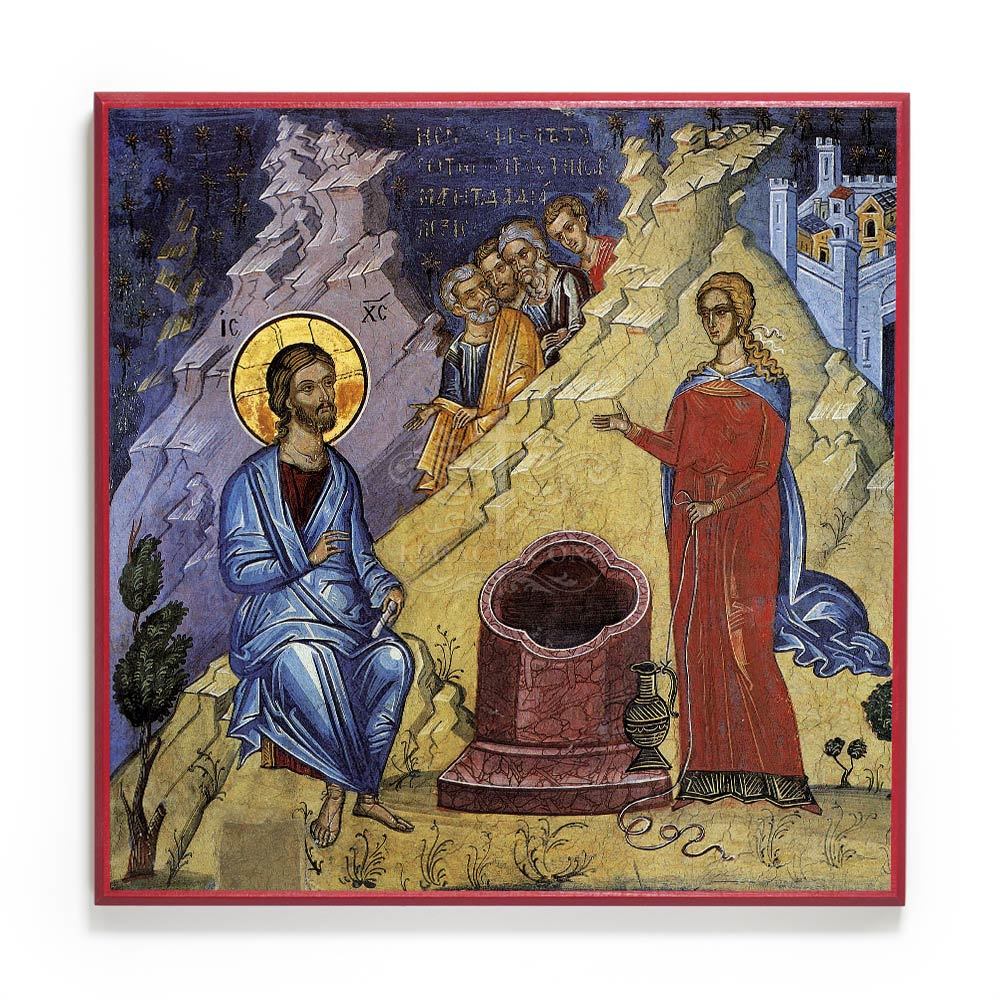

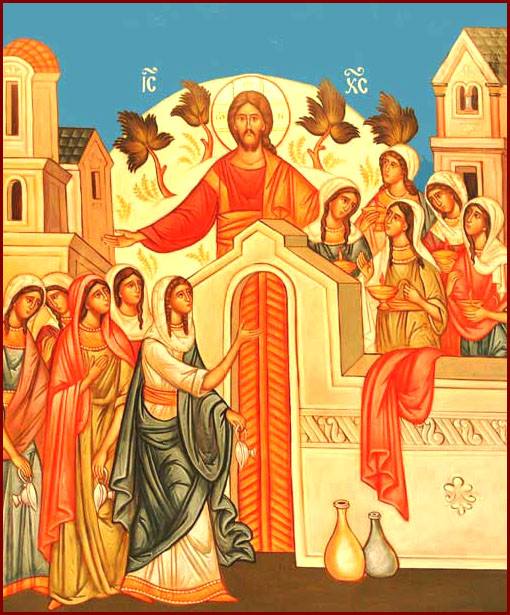

The theme of baptism continues in this Sunday’s Gospel, re-affirming that Pascha is a feast of resurrection and of baptism, being born into eternal life. The center of Jesus’ conversation with this unnamed woman (the Church later gave her the name Photine, the “enlightened woman”) is about water. They met at Jacob’s well, a place of great tradition, a sign and a promise of God’s love and mercy for his people. Jacob’s well provided the riches of water to a desert place, the sign that God would always provide for and bless his people. However, the encounter with the woman reveals something more: Jesus is the Messiah to come, he is greater than the Patriarch Jacob. The water of Jacob’s well is only for this world, Jesus would give “the water that would become a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:14). This clearly refers to our baptisms, as it comes immediately after the comparison of Jesus with John the Baptist, and the baptisms done by Jesus’ disciples

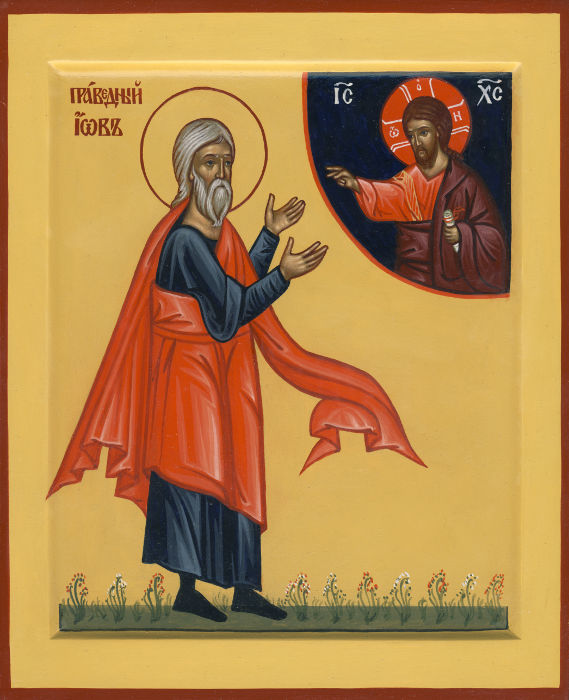

The theme of baptism continues in this Sunday’s Gospel, re-affirming that Pascha is a feast of resurrection and of baptism, being born into eternal life. The center of Jesus’ conversation with this unnamed woman (the Church later gave her the name Photine, the “enlightened woman”) is about water. They met at Jacob’s well, a place of great tradition, a sign and a promise of God’s love and mercy for his people. Jacob’s well provided the riches of water to a desert place, the sign that God would always provide for and bless his people. However, the encounter with the woman reveals something more: Jesus is the Messiah to come, he is greater than the Patriarch Jacob. The water of Jacob’s well is only for this world, Jesus would give “the water that would become a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:14). This clearly refers to our baptisms, as it comes immediately after the comparison of Jesus with John the Baptist, and the baptisms done by Jesus’ disciples The Prophet Job’s feast on the Byzantine calendar is May 6 and the Latin Church’s calendar on May 10.

The Prophet Job’s feast on the Byzantine calendar is May 6 and the Latin Church’s calendar on May 10. The Troparion at Matins:

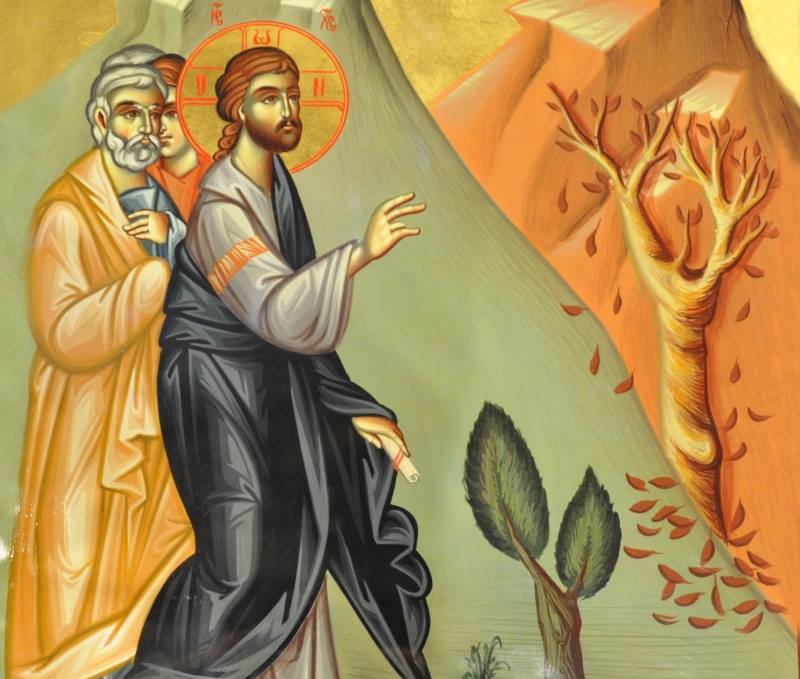

The Troparion at Matins: 2) the cursing of the fig tree.

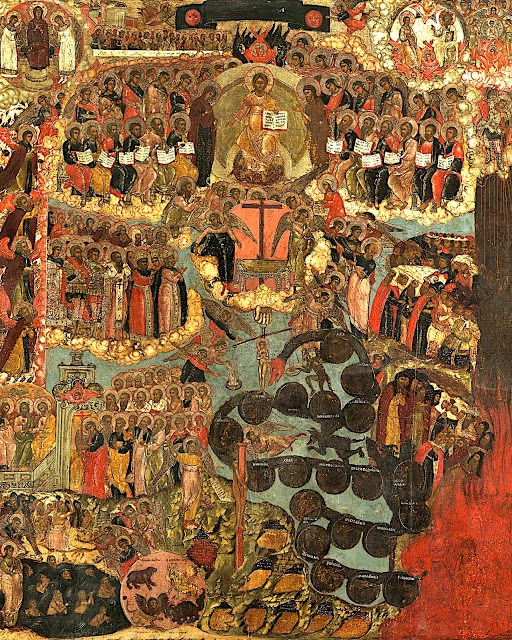

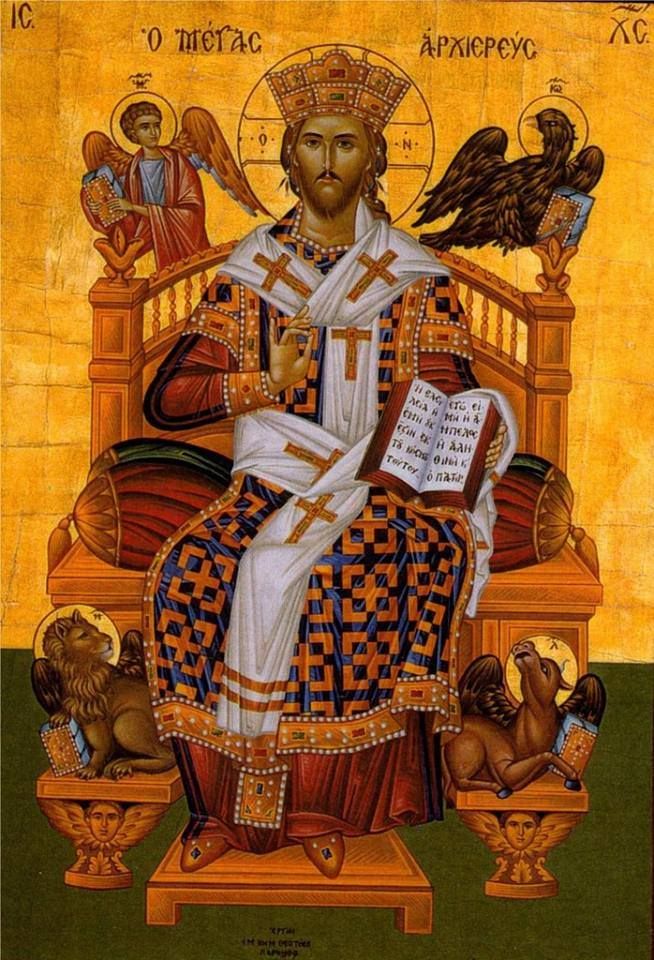

2) the cursing of the fig tree. The Roman Church has a separate feast of Christ the King in 1925, with Pius XI’s encyclical Quas Primas. It was to counter the rise of secularism by proclaiming that Christ is the only true king of the believers. The original and ancient feast of Christ the King,

The Roman Church has a separate feast of Christ the King in 1925, with Pius XI’s encyclical Quas Primas. It was to counter the rise of secularism by proclaiming that Christ is the only true king of the believers. The original and ancient feast of Christ the King,