Read: 1 Corinthians 15:1-11; Matthew 19:16-26

The Word of God: “it will be hard for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of heaven” We must not soften this saying in any way. We must ask: what does it mean to be rich? Wealth is relative. The poorest person in a first world country today has access to more gadgets and health care than the very richest at the time of Jesus. We see the problem of riches in the reaction of the young man. He cannot put faith in the Son of God, he cannot respond to the presence of God, because his heart is in his many possessions. (v. 22) Jesus teaches, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3). But the rich in spirit cannot love God more than themselves, and it is a simple reality that if they cannot love God, they cannot love their neighbors, created by God. Mary therefore declares, “The hungry he has filled with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty. (Luke 1:53) And Abraham tells the rich man in hell, “you received what was good during your lifetime while Lazarus received what was bad; but now he is comforted here, whereas you are tormented. (Luke 16:25) And James admonishes his flock, who honored a rich man, “Are not the rich oppressing you? And do they themselves not haul you off to court? Is it not they who blaspheme the noble name that was invoked over you?” (James 2:6-7).

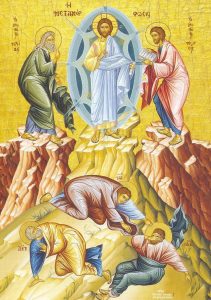

Make no mistake: riches are a scandal and an obstacle to our communion with God. Yet, in the end, Jesus always gives hope. The one who multiplied the loaves, the one who walked on water, the one who cured the boy the disciples could not cure, the one who forgave the servant who owed an impossible sum of money, the same can even do the greatest miracle and save a rich man, as the gospel today ends, “for God all things are impossible.” But it is much, much better for us if we hears the words of the Lord transfigured into glory on Mt. Tabor and who is risen from the dead. In him alone is all glory, life and love for all creation.

“Then Moses said, “Please let me see your glory!” The Lord answered: I will make all my goodness pass before you, and I will proclaim my name, “Lord,” before you; I who show favor to whom I will, I who grant mercy to whom I will. (Exodus 33:18-19)”

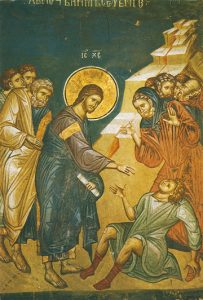

“Then Moses said, “Please let me see your glory!” The Lord answered: I will make all my goodness pass before you, and I will proclaim my name, “Lord,” before you; I who show favor to whom I will, I who grant mercy to whom I will. (Exodus 33:18-19)” Read: 1 Corinthians 4:9-16; Matthew 17:14-23

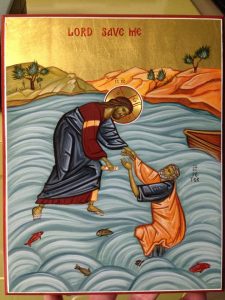

Read: 1 Corinthians 4:9-16; Matthew 17:14-23 Read: 1 Corinthians 3:9-17; Matthew 14:22-34

Read: 1 Corinthians 3:9-17; Matthew 14:22-34 In addition to the observance of the 8th Sunday after Pentecost, the Church remembers the Father of the First 6 Ecumenical Councils. Moreover, the Church also liturgically recalls the memory of the Great Holy Prince, and Equal to the Apostles, Saint Vladimir.

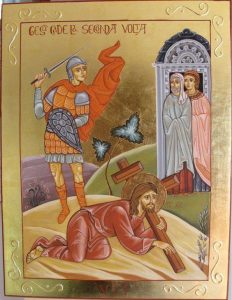

In addition to the observance of the 8th Sunday after Pentecost, the Church remembers the Father of the First 6 Ecumenical Councils. Moreover, the Church also liturgically recalls the memory of the Great Holy Prince, and Equal to the Apostles, Saint Vladimir. Read: 1 Corinthians 1:10-18; Matthew 14:14-22

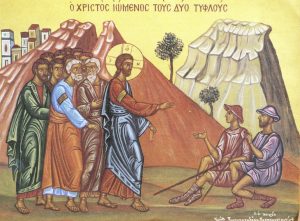

Read: 1 Corinthians 1:10-18; Matthew 14:14-22 Read: Romans 15:1-7; Matthew 9:27-35

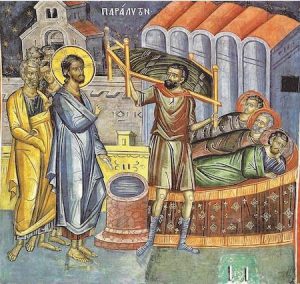

Read: Romans 15:1-7; Matthew 9:27-35 Read: Matthew 9:1-8

Read: Matthew 9:1-8